Before he died in 2007, Lance Hahn sent me some chapters from his still unpublished book 'Let the Tribe Increase'.

This is one of them.

(SOME) LIKE IT HOT

The Story Of Blood And Roses

By Lance Hahn

Blood And Roses are one of the most underrated bands in this book. Forging their own direction, like many other uncategorizable groups, they paid the price for their unique (but surprisingly accessible) musical vision.

Their story starts with Bob in Australia, a kid who’s teenage depression becomes a teenage dream with a tendency that seemed inevitably on a collision course with punk. But I might as well let him tell the story.

Bob Short, guitarist, “Ultimately, it’s a bit funny talking about why you got into punk rock. The thing is, it just kind of reflected who you were. It was like falling in love and you don’t ask why you fall in love. But why do you fall in love with one person and not another? In the case of punk, a whole lot of it came out of what you didn’t want rather than what you did.

“That probably means you are about to cop a far bigger answer to than the question you asked. What follows amounts to a standard response to this question that I just cut and paste. I get this question with every email interview I get asked to do and no-one has been interested enough to use any of it. The same goes for parts of my replies to questions two, three, four and five.

“For me, my interest in music started with Suzi Quatro of all people. As you may imagine, with the hounds of puberty snapping at my crotch, the sight of this leather clad Amazon prowling the confines of my parent’s black and white television was quite an eye opener. Nothing had had quite this effect on me except for perhaps Catwoman and Batgirl in the sixties TV show. How was I to know that Suzi was barely five foot tall? She strode the neon tube like a colossus. Her musical legacy may have been limited to a rash of early singles before her fearful decline into “Happy Days” and balladeering hell but she left her mark. There was something in the frantic pace of the music. (I later found out that the producers sped up the tapes to make them sound more exciting).

“Most importantly, there was a kind of power in the simple combination of drums, bass and guitar that made everything I thought of as ‘’real life’ up until this point seem bland and unimportant. Quite literally, I fell in love with the sound and I fell hard. By the way, I cannot stress how bland the world seemed to me at that time. I lived in a bland little bubble with fear at the door.

“I grew up in Wollongong which was a red neck blue collar steel working town about eighty kilometers south of Sydney Australia. To me, it felt that I was living on the geographical equivalent of the biggest hemorrhoid on the arse hole of the world. Though this conviction was unshakeable, I think it was shared by a great many people in a great many different locations. The arse hole of the world seemed to spread from Glasgow to Leeds and London and then into Europe and America and all points beyond.

“I’d fallen under the influence of a mob of born again Baptist Christians. My parents had wanted the kids out of the house and, what better place to send us than church. Especially since the church was quite happy to pick us up. Whether I like it or not (and believe me I don’t), this was hugely influential on my life. Just as there is no non smoker more vocal than an ex smoker, there is no atheist quite like an ex Baptist.

“These people were, quite literally, insane. They pawed over the Book of Revelations pulling proof that the end was nigh from every verse. China was preparing to destroy two thirds of the wall but no-one needed to fear because Jesus was getting ready to suck us all up to heaven if we only would believe. Their eyes were dead behind their Osmond’s smiles. They saw devils behind every action except those perpetrated by their right wing leaders. What if Nixon was a thief and a liar? It’s better to have him than to be overrun by a bunch of godless communists. If this sounds familiar, it rings alarm bells for me too. I seriously thought this nonsense was dead and buried until the recent rise of George Dubya. Once again, fat hypocrites talk of the end times and the four horsemen.

“This was all pretty powerful imagery to be laying upon a child. They told me the world was riddled with sin and inequity. The inequity was obvious, the sin less so. If the world I was living in was riddled with sin then sin was far less interesting than they gave it credit.

“Right away, you can probably see where a lot of my lyrical concerns were coming from. Incidentally, I seem to remember Lisa telling me that her father had been a minister but she didn’t talk a great deal about her growing up. She, too, did not seem overly fond of Christians.

“So, into this drab world came a little Suzi. Whilst her talk of a “48 Crash” being something like “a silk sash bash” (?????) failed to ignite any kind of political revelation, she did however start a little revolution in my head. She brought friends to the party like The Sweet playing “The Ballroom Blitz” and T-Rex, Alice Cooper, David Bowie and Slade. The guitars were loud and distorted and the songs were short and alive. The most beautiful thing I knew of was a seven inch single. Hey! Puberty was still snapping at my crotch. It hadn’t stuck its teeth in yet.

“Then, as if by magic, I came across the first record to really change my life. My parents had literally forbidden the purchase of any David Bowie related material. They had seen him on television and he looked dangerously homosexual to them. Whilst Mr. Bowie hadn’t caused the warm tingling sensations that Suzi had provoked, even I could spot that his song writing was a step or three up the evolutionary ladder from my beloved Ms Q. And, as I have said, it was the music I had really fallen for.

“So, there I was in a second hand shop and what did I spy sitting on the top of a pile of used vinyl? The New York Dolls first album clearly played once and dumped in disgust. I looked at the cover. Jesus! If my parents thought that David Bowie was terrifying, wait until they got a load of this. All this could be mine for two measly dollars.

“Now as soon as the needle hit the groove, I was changed. There was nothing in the world like this. It sounded like a train crashing through the house. Friends told me it sounded like the Rolling Stones sped up. The Stones were something out of the dark ages as far as I was concerned. I think I may have heard the song “Angie” but that had failed to move me anywhere.

“The Dolls were all flash and explosions from the howl of “Personality Crisis” to the machine gun drumming of “Vietnamese Baby”. And the words! How could anyone make songs up about this stuff? The words spoke to me so directly. I might not have had to worry myself about girl friends overdosing in bathrooms (that would come later). That feeling of alienation was easy to associate with. I knew exactly what it was like to feel “like a Frankenstein” or a “Lonely Planet Boy”. This was a kind of poetry that I could understand. There were guys at school who liked stuff like Led Zeppelin. They told me poetry was stuff like “Stairway to Heaven”. “If there’s a bustle in your hedgerow, don’t be alarmed now. It’s just a spring clean for the May Queen.” Do me a fucking favor, John.

“The next album that really affected me came courtesy of my science teacher, Miss Campbell. It was an indirect path to be sure but that’s what I was saying about influences. Well, if you were going to have a crush on any of your teachers, you might as well have a crush on the one who talks about going to see Lou Reed play. Who the fuck was Lou Reed? I hadn’t heard either Walk on the Wild Side or the Transformer album that had probably led Miss Campbell to Mr. Reed. They didn’t play Lou on the radio. I went down to the record shop to investigate.

“Sitting at the back of the Lou Reed rack was a scrappy looking black covered disc. Years of reduction stickers had bought the price tag down to one dollar and ninety nine cents. Okay, I could afford that if I skipped lunch for the next week. I certainly could not afford the more recent full priced discs. Suddenly, I was in possession of White Light White Heat by the Velvet Underground and I didn’t even know what I had. It had clearly sat there on the shelves since its initial release, unwanted and unloved. Just my kind of disc.

“Whilst listening to the New York Dolls was to take a new glimpse at this world rendered anew, hearing the Velvet Underground was like looking down a very deep hole into hell itself. How these discs crossed my path, I can’t explain but of all the record collections in all the world, they walked into mine.

“Politically, Australia was going through some pretty major changes. After an eternity of conservative rule under the “Liberal/National Party Coalition”, the Labor Party had taken the reins of power. Australia pulled its army out of Vietnam. A national health service was introduced for the first time. The whole country seemed to be being dragged out of a post war time warp kicking and screaming. Maybe there was just a chance that the world was going to get better.

“This feeling of change and hope was short lived. The coalition controlled senate blocked supply to the government’s budget. The Governor General (who is the Queen’s representative) stepped in and fired the government and Australia went tumbling back into the nineteen fifties. Imagine what would happen in the UK if the House of Lords refused to pass the budget and Queen Elizabeth sacked her government. There were demonstrations that did little against this establishment closing of ranks. Most Australians didn’t really like all this change that was going on. The cities protested but the great rural centre shifted back to the right.

“The protests did, however, mean I met people who claimed to be anarchists for the first time. They were older than me and so I didn’t really get to hang out. Most of the protests came from Socialist and Trade Union groups. Whilst the socialists talked exactly like the Baptists, constantly reciting from received dogma, the trade unionists had the typical arrogance of old men who thought youngsters needed a haircut and a kick up the arse. The anarchists at least seemed alive and funny. This was 1970s Australia, however, and they were a little overly obsessed with notions of rural communes and decentralization received via the doctrines of Chairman Mao and a cloud of dope smoke.

“Meanwhile, even the music sucked. Abba held endless reign over the charts. Their single “Fernando” held the number one spot for sixteen weeks. Glam vanished up the Bay City Rollers collective backsides and what a tartan clad atrocity that was. The hip kids listened to America and the Eagles and that mind numbing heavy metal crap played by show ponies in strutting flares. Once you’d listened to “Sister Ray” a few times, Deep Purple prancing around singing “Smoke on the Water” was patently ridiculous. I did not want to go through the desert with a horse with no name, visit the Hotel California or take a trip to the Dark Side of the Moon.

“Now one thing I have learnt is that the world can’t stay that boring for long. My first hint that things were changing came when I saw the Runaways on television. Say what you like about Kim Fowley and his media manipulations, the “Cherry Bomb” video was incendiary. Not just because of the all female band but because of the energy. Almost immediately, you started hearing about bands like the Ramones and local bands like the Saints and Radio Birdman. Then, obviously, there was the Sex Pistols and it all gets a little obvious after that.

“But really, it seems everyone attempts to deny the influence of the Pistols, The Clash and their ilk but that is just ridiculous. Whilst the Pistols without Lydon were an embarrassment of such epic proportions as to all but taint reputations entirely, no-one could deny the power unleashed by “Anarchy in the UK”. The kind of anarchy that was being advocated may have been little more than drunken nihilism but there was at least a modicum of political awareness and education behind it. The tabloids may have written the scene off as morons wallowing in their own vulgarities but the interviews told a different story.

“Likewise, The Clash may have jumped on the CBS bandwagon with a clutch of lyrics that merely spewed venom back at the vileness of the world but their involvement with Rock Against Racism set the political agenda.

“But the rise of these (and lesser known) groups did something else. Suddenly you realized that there have been a whole lot of people all over the world thinking the way you think, listening to the same music and sharing the dreams that you have. If there is one freak in every school in the world, that adds up to a whole lot of freaks in the world. And when those freaks got together, there was going to be a hell of a party.

“I had been spending my nights in pointless acts of vandalism. Well, not pointless. There would always be a plan. The idea was the important thing. Looking back, I think I should have applied for art council funding for these little events and installations. These included building walls across suburban streets with bricks plundered from local building yards; relocating cars between trees (you had to get a group of five or six people to pick it up and carry it); systematically scratching every copy of Abba’s Arrival at the local K-mart; casting down a storm of milk crates on the local bowling green and pouring petrol over a local creek and igniting it (you want to see Smoke on the fucking water?).

“Whilst these acts seem ridiculous in hindsight, it is only now that I realize how interconnected they are to my later “artistic” pursuits. I don’t think I was particularly special or unique in this. Certainly, a lot of the anarcho punks engaged in vandalism as part of their identity. For example, Martin of Faction had a personal crusade to superglue the locks of every butcher shop in London whilst graffiti was considered our only legitimate means of communication with the masses. What tight suited bank clerks made of anarchist slogans is difficult to say. One would probably guess that the only influence such messages had was entirely negative.

“My t-shirt collection had been getting me in trouble at school long before I’d even seen the works of Westwood and McLaren. The sacking of the Labor Government inspired my hand drawn “Fuck the Monarchy” shirt which had earned me a beating courtesy of a Vietnam Veteran PE Teacher. Not deterred in the slightest, I came back with my masterpiece. The Sunday Telegraph was proud to include an Abba iron on T-shirt transfer so you could make your own Abba t-shirt. I discovered that a pair of scissors and a little rearrangement of heads and letters could work wonders. The “Abba are shit” t-shirt was born. To my teachers, this proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that I was in need of psychiatric help.

“The fact that I’d gone to war with the English department didn’t help. Asked to review Orwell’s 1984, I had described it as a satire of post war Britain and political allegiances. The teacher told me I was wrong, called it a dystopian fantasy and gave me five out of a hundred. It didn’t matter to her (or indeed Crass for that matter) that Orwell had initially wanted to call the book 1948. I was wrong and she was right and war was declared.

“The next book up was Jane Eyre which I figured there was no point in reading. After all, the teacher was going to hand out notes on what she thought the book was about so I based my next review entirely on that document. Suddenly I had a mark of ninety nine out of one hundred and a pat on the back.

“’How did you improve so much?’ she asked in front of the class. And so I told her the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. I ended my reply with ‘thus proving my original assessment of the book “1984”, QED.’

“Now I had my very own school psychiatrist who would come and make weekly visits. He would tell me not to worry. I wasn’t crazy but they were. This was mildly reassuring though slightly disappointing. Everybody else who got sent to him ended up with scripts for all manner of mind altering goodies.

“Finally, my English teacher decided it was time for drama. She beseeched us to act out an escape. (Was she asking for trouble or what?). Kids huddled around walls under the gaze of imaginary spotlights. They crept under tables. They pretended to escape whilst escaping nothing. It was my turn and - you could feel everyone was just waiting for what I would do (the English Teacher War had been long and bitter) - I stood up, smiled and waved and walked right out the door - and out of the school - and out of Wollongong.

“It was 1977 and I was going to be in a punk band.

“The Sydney scene was pretty much dominated by Radio Birdman who mined a musical vein somewhere between the Stooges and the MC5 whilst lacking the nihilism of the former and the political edge of the latter. That shouldn’t be taken as any kind of criticism. This was a band that had decided to do what it was doing without the input or constraint of peers. They picked an unpopular road and beat their heads against it until people started listening.

“I particularly liked the way they thought. No-one will book us so we’ll start our own club. No record company will touch us so we’ll do it ourselves. Whilst that became a fairly standard avenue to follow over the next couple of years, these were amazing ideas at the time; the notion that you didn’t need to wait for permission.

“In Brisbane, the Saints had pretty much done the same thing. Their self pressed “(I’m) Stranded” single hit the shelves the day after the Ramones LP. The UK bands at the time were all hanging out for major labels. The only place the Saints could play was in the front room of their house. Nobody would have them. Live, they were amazing. I remember sitting outside a hall listening to their sound check. Just the sound of the Bass drum sent shivers down my spine. Finally, they hit the stage and just ploughed through their set. They stood there looking like men braced against a storm, screaming feedback against the wind.

“One of the biggest influences on my life has been this notion that you do what you do no matter how many times you’re told to fuck off and die. You don’t do it for fame or recognition or money. You do it because you don’t have any other choice but to do the work.

“Arriving late from Melbourne came the Boys Next Door but their initial appearance in Sydney was met with howls of derision. They arrived as the headline act of a Melbourne New Wave package tour for Suicide Records. One of the majors had decided to cash in on the punk boom and create a specialist imprint. The resulting compilation was everything you’d expect of a corporations idea of what punk should be. The one exception was the Boys Next Door’s version of “These Boots are Made for Walking” which wasn’t without charm. I wish I still had my copy because the band’s famous singer is so ashamed of his murky past that he refuses any chance of re-release.

“Live on stage, things weren’t quite so rosy. Singer Nick Cave (for it was he) copied every Bowie gesture he could think of including miming his way through the invisible wall. To make matters worse, two of the support acts had had their singers attempt to pull the exact same stunt already that night. If nothing else, this provided a good lesson in what not to do on stage.

“Having said that, when the Boys returned a year later, they were a different - and spectacularly original band. A year after that they would wash up at The Rock Garden in Covent Garden under the name The Birthday Party and I guess the rest is history.

“The turn towards more political bands was slow in Sydney. Johnny Dole and the Scabs flirted with Clash like political lyrics but their set was bogged down by pub rock style covers. They played more Rolling Stones songs than originals. Towards the end of their run, they had cut most of the flab and packed a considerable punch. They never quite rose above their less than fabulous beginnings.

“X (no relation to the similarly named Los Angeles outfit), sung songs about low lives and the shit that rained down upon them. Somewhere out in the Western Suburbs, The Last Words cut a single called “Animal World” that seemed to come from a world somewhere between the Jam and Sham 69. My favorite band were the Psycho Surgeons who played like a feed backing chainsaw let loose in an abattoir. They had songs with titles like “Crush” and “Meathook”. Their set lists were just a column of single words. Radio Birdman singer Rob Younger once gushed that this “represented the kind of minimalism that the Ramones could only dream about.” He wasn’t far wrong.”

With the backdrop of the crazy outlaw days of early punk in Australia, Bob began playing music in a series of confrontational punk groups.

Bob, “The first band I was in was called Filth. I’ll let someone else write about us. I don’t know who wrote this. A friend who collects fanzines came across it and it seems to come from the inner sleeve of a CD. I don’t know what CD it is and neither does he... It originally had a rather fetching photo of me revealing a scratched up chest but - as I posses a photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy, there is little point in me scanning what is left of the image.

“‘Spewed forth from thin air (no-one really wanted to own up to aiding and abetting them) were Filth who took their moniker from the spectacle of a deserted table in McDonalds covered in half eaten food. Featuring guitarist Bob Short, barely in his fifteenth year, and vocalist Peter Tillman who would later front the Lipstick Killers so commandingly. Filth had to do only ten shows or so to make it into the history books. Arguably the most anarchic, downright dangerous band to take a stage in this country, reports circulated widely of gigs dissolving into violence, with audiences on the receiving end inelegantly thrown mic stands.’

“All this is basically true except for the McDonalds story. Having decided to form a band, we went to the family restaurant in question to work out a suitable name for our little ensemble. This proved more difficult than I had given such things credit. I began to amuse myself by safety pinning the disposable tinfoil McDonald ashtrays to various parts of my anatomy. (Hey, don’t get the wrong idea - none of them went south of the Equator.)

“Suddenly an irate woman came running towards us, grandchildren clenched tightly to her side. “You’re Filth!” she cried and who were we to disappoint? As for being anarchic, the anarchy was more nihilist than anything else - though there was a definite political consciousness developing in my songwriting. To me, the songwriting was the most important thing. Learning to play guitar was a way to let off steam. Writing songs was something else. Something (and I use this word advisably) magical. I figured if something could just appear in your head like that, you had a duty to share it with others.

“The first song I wrote was called “In Love” and it appeared like a gift as I was walking down the street. By the time I got home, it was all worked out and it didn’t really bother me that it sounded like something rescued from The Velvet Underground’s waste paper bin. The lyrics, however, were a bit of a worry. I wrote several versions - some in which I was in favor of this love thing and others that were not. Later on, it evolved into “Fall Apart” which Blood and Roses would play but not record.

“Responding to my poor showing in the lyrical stakes, the next song I managed to pull out of my hat was called “Do the Harold Holt”. Now I was getting somewhere. Harold Holt was an Australian Prime Minister who went for a swim and didn’t come back. Here was something that didn’t sound like somebody else’s songs. It didn’t matter to me if it was shit or not. It was my shit.

“I followed on with songs like “America get fucked”, “Curse on You”, “Thalidomide Child” and “The Law is your Friend.” It was only when I wrote “Jesus” that I had a song bounced back at me. I couldn’t understand why people took such offence to slagging off religion. It also pointed to a greater schism within the band.

“Whilst bathing in the attention that arose from singing songs about the slaughter of politicians, singer Peter Tillman really wanted to sing about cars and girls. Preferably, the girls should be armed with chainsaws and drive converted hearses to the beach but you get the picture. And don’t think I’m going to knock him for that. His next band, the Lipstick Killers, were a damn fine outfit. I just wanted to pursue the lyrical course I was taking. I thought of the mayhem we were creating as a kind of cultural terrorism. We would do anything to get a reaction. Pete once said that this was a band that destroyed people’s (the audience) lives.

“It all came to a head when we went on tour supporting the Psycho Surgeons. After a performance of sheer noise attack and audience abuse, we found ourselves banned from all the venues we were due to play at. Everyone was getting on each other’s nerves and the Psycho Surgeon’s were desperately in need of a singer who could sing.

“Returning to Sydney after the debacle of the Adelaide gigs, I formed “The Urban Guerillas” with Andi, Ross and Johnny Gunn. There’s another band now doing the rounds in Sydney with the same name but have nothing to do with us. At this time I think we could have been described as an Anarcho punk band. The political themes hardened up. Anti war. Anti Government. Anti Religion. We called ourselves punks. We looked like punks. We were unified in that kind of identity. There was a kind of safety in numbers. Everyone looked at us as if we’d come from another planet (and not in a nice kind of E.T. way). The villagers would light their torches and start sharpening their pitchforks when we walked by.

“Whereas people like Johnny Rotten mocked later punks as clones and copycats, I always understood the need for an environment that allowed people to express their individuality. Plenty of people involved in the later day punk movement came out of dysfunctional families and abusive households. They were orphans in a storm looking for a family. The criticism by punk’s elder statesmen really arose from the selfishness of their concerns. It was not as if they hadn’t copped much of their style out of what had gone before them. Whilst this was widely felt, I think it was poorly articulated.

“From mid summer in 1978 to February 79, the Urban Guerillas pretty much played a once a week residency at the Grand Hotel at Railway Square. It was the only venue that would book us. Pretty soon we had a fairly large, unique audience that really looked and acted punk. None of the other venues really wanted them either. By the end, we were playing to about two hundred people a night.

“Our set included such songs as “Paradise”, “No Allegiance”, and “Mummy”, all of which later turned up in Blood and Roses’ set. Other songs included “The End of the Western World” and “Smash your TV”. To be honest though, there are about fifteen to twenty songs from this period that I have completely forgotten. At one stage I had a book with over a hundred and fifty potential songs with lyrics and crude chord structures that never got near a rehearsal.”

Having at that point exhausted the punk rock resources and interest level in Australia, like the aforementioned Cave, Bob relocated to England.

Bob, “A little from column A and a little from column B. Whilst the Urban Guerillas were probably a band that could have been successful, my own self destructiveness was on the rise. If I caught sight of the nose on my face, I saw no logical reason not to cut it off. There were some personal problems that amplified everything in that heightened teenage kind of a fucked up way. Relationships fucked up. There were people I didn’t want to see. However, whilst on one level I had the desire to run away, there was also the desire to run towards something else. It was a match made in heaven, literally, one day, I went to a party and I just got bored. I was fed up of the same old faces and the same landscape - not to mention the same fucking cops hassling me on a daily basis. I should have got drunk but I didn’t think that way. The next day I booked a plane ticket without even knowing how I’d pay for it.

“I had been born in England and I still had a British passport and London seemed the logical place to go.”

Despite some of the obvious similarities, London was a very different place from anywhere in Australia. Instinctively, Bob was drawn in and eventually drifted into the intense squatting scene of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s eventually embroiled in the small p and capital p politics implied by that lifestyle.

Bob, “My first impression of London was that I had discovered the fall of the Western world. It was like standing on the edge of some terrible maelstrom watching all the shit on Earth falling into oblivion. Of course, I always had a flair for a dramatic turn of phrase.

“London, of course, was a very different world than Sydney and that was a very different time than today. It was violent, squalid and down right dangerous to know. The music scene was as it always is. There are always a bunch of perverted money stealing morons running the show and, if you want to get on, you are expected to kiss butt with tongue. Talentless hacks get all the good gigs and the shop is locked up tighter than a fish’s bottom. If you want to do something, someone is always willing to help if you’re ready to pay the price but there are always no promises.

“Business remains as per usual.

“I rolled up in London with a guitar and empty pockets. Ultimately there was only one life style choice available and that was squatting. People didn’t squat for any one reason. There were older ex-hippy guys who squatted simply because they believed property was theft. There were kids who had run away from home. There were drunks, junkies, lunatics and the great and glorious freaks of nature. If I had to choose one answer on a multiple question test, I’d have to tick the box that said “I had nowhere else to go”.

“Squatting was fun and terrifying, sad and boring. It was like living in an X-rated version of Coronation Street or East Enders. There was sex and drugs and rock and roll. There was also squalor, disease and death. I felt feelings of belonging and community I will probably never feel again but there were also times marked by emotional pain and loneliness. We had nothing but each other’s company but sometimes we hated each other’s guts.

“But squatting firmed whatever you did into a lifestyle. There was no dressing up at the weekend. There were no excuses like jobs, families or pets. If you were going to something you had to do it. I’ve always been a doer and now I was surrounded by doers. There was people who didn’t talk to you like you came from another planet just because you were different. There was no place better to be.

“Different squats had different vibes. It’s difficult to, say, compare the Fire Station at Old Street with Campbell Buildings in Waterloo or Derby Lodge in Kings’ Cross. Different people, different music and different drugs. Two months was a long time in London. One day everyone was doing speed and listening to the Ants and then suddenly we’re all dropping Valium and someone upstairs is playing Public Image Limited’s “Theme” over and over and over again. There you are, too off your tree to go upstairs and change the disc and someone has crashed out with the bar on the record player up so it is on eternal repeat. Twenty four hour a day exposure to John Lydon wishing he could die can have devastating effects on the human psyche.

“‘We have nothing to fear from chaos, we have always lived in holes in the wall.’ It’s almost definitely misquoted and I forget who said it but the point is obvious. Poverty is a great politicising force. Whilst the working class were growing enough enfranchisement to vote Tory at the general election, an underclass was growing. In many ways, the system encouraged it. If you were on the dole, private rental was not an option in London and council housing was primarily targeted at families. If you were young, broke and pursuing any kind of alternative lifestyle, the system had no need or place for you. It wasn’t like there were jobs going anyway.

“Besides, who wanted to work anyway? If you worked, you made someone else rich. You were just contributing to your own oppression. I am shocked at how alien a concept that sounds twenty five years on. Whilst it was not a popular opinion with those in employment, it was certainly common coin in the squats.

“Now I wouldn’t want you catching any kind of notion that the squats were one big anarchist utopia because they were not. The great schism in punk at the end of the seventies was between the extreme left and the extreme right. The choice was between a society should be run by a consensus that respected the individual (who we shall call anarchists) and those who believed the society should be governed and governed hard against the individual (who we shall call Nazi scumbag bastards).

“Prejudiced? Who? Moi?

“Fascism holds an equally great attraction to the underclass underdogs. People can find identity, family and purpose in it. Without a suitable moral compass, many succumbed to this vice. The ill-defined rage and nihilism of the first wave of British punk had all the advantages of energy but its lack of clarity of intent bought about conflicting ideologies.

“If you set out to destroy past morality and offer a void in its place, then that void will be filled. When Nietzsche declared the superman who was beyond good and evil, I seriously doubt he intended Hitler to invoke his philosophies whilst running extermination camps. When Johnny asked “when there’s no future, how can there be sin?” I doubt he expected that some would take it as license to rape, kill and pillage.

“Then again, I knew one guy who took the lyrical content of Crass’ Penis Envy to mean that women essentially wanted to be beaten and mistreated. Suffice to say, this man was not a close personal friend of mine but his leather jacket was coated in the thick scrawl of anarchy signs and dogma.

“Art is a dangerous thing and the only way you can truly take responsibility for your actions is to do nothing. (Which, of course, involves making an active choice which means you are actually doing something so you’re fucked whatever you do.)

“The British Movement seemed to be the major political allegiance of the skinheads. They considered the National Front to be too wet and suggested its leader was a homosexual. This was an interesting complaint given these men’s attacks on squats in Camden Town and Kings’ Cross that, in addition to the usual carnage, involved the sexual assault of men. Not to mention the fact that - some years later when I went to see Test Department play at the gay nightclub Heaven - I saw a fair few of these ex Nazi boys involved in quite a different lifestyle choice. Funny that.”

Simultaneously in the squat scene, Lisa Kirby (now Lisa Burrell) was getting interested involved in music and other extracurricular activities of a less legal nature.

Lisa, singer, “I don’t think I did get into music, it was always there. I can’t remember a time I didn’t love music or dance make up songs. Well the time punk came it fit me like a glove, seemed the attitude was mine. Before punk had been into the black scene down the west end, at 15 I loved James Brown, Big Youth, Blues clubs was out all weekend just dancing. They used to call me and my friends The Sunday School Outing and they weren’t too far off the mark , all from an all girls, High church of England school we were more used to reeling off Latin chants every morning at assembly than doing The Latin hustle down Soho (a dance by the way.) all weekend. I loved the bass and rhythms plus the volume but the attitude stank towards women and the white people with their fake Jamaican accents made me laugh but it all used to wind me up as well. I was full of rage but pretty insular, mucked about with Ouija boards, stopped going to school, went sticksing with a couple of black guys I knew (pick pocketing.) the sticksmen used to always wear burberry back then, things don’t change much.

“Punk came along and it was all brand new but far from shiny and scared the record business into taking chances was brilliant. I went down the clubs on my own as everyone I knew were still into the same old stuff.

“The first club I walked into was The Vortex down Wardour Street. It was like walking down those dark steps was it. White faced, black eyed, black lipped and black heart. Was like walking through a very warped looking glass and it felt like home to me.”

Lisa’s musical career started with a groups that existed in every except for having a note of music. Perhaps post-modern in retrospect, it just showed the desire kids had to start a band long before they had the technical ability.

Lisa, “I was always into any form of expression; it was a necessary release for me. Was a very quiet person until you got to know me and that usually took awhile. I needed to release myself in other ways. I drew, danced wrote words down just as a way of hearing myself think sometimes. I think I sang out loud rather than talked out loud because it didn’t seem as weird and for some reason I thought that when people looked at me they could see that I was strange. At least when I got into punk I could tell myself it was the clothes and make up they were looking at. So I asked just about everyone I had a halfway decent conversation with if they wanted to start a band.

“Me and a friend of mine did such a good spray campaign people were looking to interview us. We didn’t even have a band just a name. The Necrophiliacs, we should have chosen something shorter, took too much paint and too much time to write it.”

At the same time, Bob had a theoretical group of his own happening. This group would eventually evolve into Blood And Roses.

Bob, “I was squatting in a world of squalor, poverty, police harassment and an undeclared war against Nazi skinheads. I met Ruthless (aka Ruth Tyndall) at the squat in Old Street. She had a bass and I had a guitar and a pile of songs. There was a guy called Jock who had threatened to sing with us and his mate Beano could allegedly play drums. A band in theory, yes. We could certainly wander the streets of London and claim to be in a band but we never played or rehearsed. Jock went off to join the bloody army which seemed a damn peculiar choice for a skinny Sid Vicious clone. Time passed and Ruth and I found ourselves washed ashore in Campbell Buildings SE1.

“This was where we met Lisa (Kirby) and Richard (Morgan) and the band that would become Blood and Roses really began to take shape. We began to learn the songs in peculiar acoustic rehearsals. At the time we called ourselves. We deliberately decided we would not have a name on general principle. We had a symbol that was like a hammer and sickle barred by a swastika and formed into a question mark. It provided the opportunity to bombard a variety of sites with some mind fucking graffiti but we were low life scum - literally street people - and no one was going to let us anywhere near a venue.

“If asked, I think we would have all called ourselves anarchists. I know that I did. Richard’s notion of anarchy was probably a little different from my own and probably fell more towards nihilism. He was certainly the only member of the band who believed that getting a record out would lead to ownership of the kind of automobile that would make him “irresistible to the ladies”. I paraphrase there but - y’know - he was the drummer after all.

“We had no amps. Just instruments and no-one in their right mind wanted to let us anywhere near there’s. It wasn’t like we were going to fuck with them deliberately but I think our fellow musicians looked at us in the same way as you wouldn’t give a child a gun to play with.

“Finally, at the start of 1981 we got a gig at a pub in Bethnal Green. We were so dreadful that someone should have taken us out the back and put us out of our misery. We plodded through about eight of our ten song set, unable to hear each other. After trying to get it together for a year and a half, we just fucked it. Ruth made the sensible choice and left the band and abandoned the self destructive lifestyle.

“It took about another six months to pull ourselves together again. Richard bought in one of his drug buddies to play bass. He came from Clapham and his name was Clapham and we musically, we improved for a while. We had started using a lot more rolling drum patterns and spidery guitar lines. Clapham’s lines also began to become more intricate and the music began to lose cohesion. There was nothing to hold onto.

“We would have worked something out but personalities began to clash. Clapham was just too damn straight. I always thought he looked down on us as freaks he could slum with until his real career took off. I really don’t think the rest of us had anything else we could do. We had dug ourselves so deeply into the life we had, there was no turning back. We played one gig in Clissold Park, Stoke Newington. They wouldn’t let us play without a name so at the last minute I said call us “ABCDEFG” because the Cramp’s song “Under the Wire” was playing on the stereo (technically the mono) and Lux gurgled that line out at the appropriate moment.

“With Clapham ejected, Lisa found Jez (James) and he wanted to play like a Ramones, I had no objections. Our first gig (under the name Blood and Roses) was at the Anarchy Centre in Wapping on the first Sunday in January 1982. Ten days or so earlier, on Christmas Eve, a gang of skinheads had broken into the squat on a smash and injure mission. Some things never seemed to change.”

Lisa, “Myself and some friends had moved into a block of squats in waterloo and were setting up house, new people were moving in all the time, there were plenty of flats and loads of different kinds of punks, it was a really good mix loads of characters and a really good mix of music came with them.

“Ruthless and Bob turned up. Ruthless and I became good friends, and then just got to know Bob too. They had a singer but things didn’t work out and then I had a go.

“Was very unsure of myself at first and after all those plans I had when it came down to it I was petrified. Bob was brilliant though and he worked with me through the songs I guess he must have known how nervous I was because he was just really patient and gradually I pushed a voice out.”

With the band largely propelled by Bob’s will at the start, he also was the one to pick the name.

Lisa, “The name was nothing to do with me, Bob picked the name. It was so much more Bobs baby in the beginning.”

Bob, “The name came from Roger Vadim’s 1962 film of that title. A version of Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, I remember it mostly for its hallucinogenic central section. Obviously, we were looking for a different kind of a name than everyone else. I was taken by the poetic sound of the phrase. To me it suggested not just a darkness and a passion but a beauty too. There is an obvious menstrual connotation there to which, hanging around “witchy types”, I was quite drawn to.”

While the only true title that can be bestowed on Blood And Roses is “squatter band”, revisionist history often puts them as being involved with the goth, death rock or Batcave scene which the band actually preceded. What with some of the Crowley inspired content and the often creepy crawly guitar playing not to mention the growing interest in more tribal rhythms, it’s an easy mistake to make.

Bob, “It would have been a little hard to set out to be a goth band or a death rock band before these phrases were coined! In the end, it doesn’t particularly matter what people call us. You ultimately don’t have much choice about the pigeon holes others will try to find for you.

“I think we started as a punk band but that we initially sounded a lot like a Sydney punk band as opposed to a London punk band. That kind of set us a little apart right from the get go. Then we just began to grow from the original seed into something else. By the early nineteen eighties, there were a lot of different kinds of music around to influence us. Perhaps we generally moved towards a darker edge and if people want to call that goth or proto goth, I don’t really care.

“The only relationship I tried to have with the Bat Cave crowd involved chasing women dressed like Vampira or Morticia Addams. Sure, I went there but I also went there on nights where different club nights were happening. I felt no attachment to the scene and I hated the way thy would leave people queuing down into Dean Street as the door bitches worked their go slow policy in the name of cool.

“I think some of the Alien Sex Fiend songs are pretty funny but they never really rocked my world. I thought of them more as a vaudeville routine. I’m not knocking them. I quite enjoy certain vaudeville acts. I don’t think Blood and Roses were a vaudeville act.

“We weren’t entirely po-faced. “Curse on you” was kept in the set because it was funny. Even when I had written it as an unpleasant teenager, I probably meant the anger but expressed it with tongue clearly pressed to cheek. Other material was very serious.”

With that same sentiment, it would be hard to call Blood and Roses an anarcho punk band in the obvious sense. But with their involvement in the squat scene, their regular gigs at @ centres, their lyrical content and Bob’s relationship with the Kill Your Pet Puppy group, they were by default as involved as the Mob or Flowers In The Dustbin or the Apostles.

Lisa, “The bottom line really was finding a place to live, getting water, electric, food, drugs and music keeping on doing what you’re doing and meeting others who pretty much did the same. As soon as someone puts a label on something it creates a division.”

Bob, “As I said, I never referred to us as any kind of a band. I don’t really think we fitted into any convenient package. Our first gig as Blood and Roses was over at the Wapping Anarchist Centre and, when we played there, we didn’t sound out of place. They were without doubt the best gigs we played. That was where we felt at home. They were the people we liked playing to. We were squatting in the same squats and hanging out together all the time and talked about the same crap. Andy Martin of the Apostles lived just around the corner and the Mob were just a slightly longer walk away in Brougham Road. I can’t see any reason we would have thought of ourselves as out of place or different.

“It is only in hindsight that people are desperate to work out who was in what category.

“My very favorite gig was at Centro Iberico when we got up at the end of the night to play a short set because we were all there. We played three songs and the whole place just exploded. In the gaps between songs, the roar that came back seemed louder than the band. It was like some giant animal roaring at us. That was cool.

“Playing the Anarchy Centre was not without consequence. Whilst we got the odd gig at the Moonlight and a few pubs here and there but the circuit remained closed to us. Later, I was told that this was because we had been one of the Anarchy Centre bands which had allegedly pulled the crowds away from the Lyceum and led to it’s closure. We had been black listed.

“Of course, that story is stupid. The A centres rarely pulled more than a crowd of two or three hundred people no matter what anyone says. You wouldn’t have been able to fit many more people into Wapping if you tried. Of course, these days, if some of the tales I hear are true, the Anarchy Centre must have been double the size of Wembley. The Lyceum’s decline was the fault of management. When your premier acts are the UK Subs, The Exploited and the Anti Nowhere League, you are really trying to run an empire off of the laws of diminishing returns.

“Besides, you would have to pay me to go and see the Exploited or The Anti Nowhere League and you would have had to pay me well. I was not alone in this notion.”

Bob and the group were part of the anarcho scene almost by default.

Bob, “This was where I lived. This was a scene that wasn’t there to start with and grew up around the people involved and that included me. This wasn’t something I sought out, I just found myself there. It was a damn exciting scene to be in because it was filled with talented (and some not quite so talented) people who shared an enthusiasm to create something. We didn’t come out of middle class art schools and nobody’s daddy was in the wings paying the bills. We all started on the level playing field of having less than nothing and it didn’t even phase us.”

With this broad appeal, the group found themselves playing with a wide variety of bands from the anarcho groups to the proto-goth groups to post-punk units.

Bob, “Oh, you know what it’s like. Sometimes you play good and sometimes you play not so good. There wasn’t a whole lot of fold back so it could be fairly difficult to work out what we played like. From the moment we started playing, people started jumping around and that was a good thing.

“We played with the Mob and Part One. We played with the Apostles, the Witches and Oxy and the Morons. We played with the Sisters of Mercy and UK Decay. We played with The Sex Gang Children, Brigandage and the Damned. We’d play with anyone who was happy to let us share a stage with them (and quite a few who were not). Once we rolled up to find a whiny little loser had nailed himself to the front of the stage and was going to play regardless. He turned out to be Billy Bragg. I’d like to tell you he was brilliant but I got so bored that I walked into the other bar to watch Culture Club on the Video juke box.

“Personally, I didn’t care who we played with. I always maintained the arrogant notion that when we had the stage it belonged to us. We were more than happy to share it with members of the audience but we never thought in terms of us supporting anyone or them supporting us.

“People would turn up to see us and then either leave or cause trouble for any bands that followed. This would further jeopardize pub support gigs. Once we were playing at a pub near Earls Court supporting the highly touted Playne Jayne. We played and left. The audience demanded Playne Jayne get off the stage and let us back on. Windows were broken and furniture smashed. It was a rare instance of being banned from a venue even though we were already on the 73 bus and half way back to Stoke Newington.”

Bob was also getting involved in the aforementioned Kill Your Pet Puppy collective. While the title “collective” may have been largely bestowed upon them by the outside world, the group did revolve around the fanzine of the same name.

Bob, “I don’t think there was really anything you could really describe as a Kill your Pet Puppy collective. It was more a social group than a collective in the “Crass” sense. This is something you should really talk to Tony D about because, although I knew everyone who wrote for that fanzine and hung around with them socially, I was at no point involved in the production of that magazine.”

But many of the interests of the Kill Your Pet Puppy group started to come up in Blood And Roses interviews including revisiting punk’s relationship with the Situationist International.

Bob, “Well, I don’t think we alluded in interviews. I think we quite openly discussed these topics and therefore they obviously affected the music and the group. On one level, we were clearly affected just through lifestyle and the social groups through which we moved. We alluded to some of these things lyrically whilst other things were sung about more directly.

“A song like ‘Paradise’, though more poetically phrased than many of its genre cousins, is clearly about what I disliked about ‘normal’, nine-to-five, nuclear family wage slavery. It is a straight forward text. A song like ‘Necromantra’ needs to be scratched at to decipher meaning. A song like ‘Spit on Your Grave’ probably needs a road map.”

While these ideas were implicit with the group, Lisa found it best expressed through the music and less through interviews.

Lisa, “Ahhh! Interviews, I always thought it wise to keep my mouth shut and this is pretty much the first time I’ve ever taken the time to say anything. You can probably tell by my grammar.

“There was always much talk and it’s good to shift a few ideas around but it’s like once someone has printed them you’re stuck with them. And then someone sticks a label on you and puts limits on you.

“I really just like to take each situation or day as it comes and do the best with it that I can.

“Blood and Roses were a group of four different individuals it would be impossible to say that we were all on the same track; we made music together and added to the mix until it had its own sound our attitudes were tuned on that level and that’s pretty much all that mattered.”

In attempt to somehow label and therefore find a place in history for this new generation of groups, the NME promoted the notion of Positive Punk of which Blood And Roses were unwittingly involved.

Lisa, “I haven’t got a clue. Positive Punk was probably something that sounded good; I know I didn’t come up with. It was a title for a piece in the music papers which we read then got on doing what we were doing.”

Bob, “Well clearly something was happening musically as 1983 raised its ugly head but it didn’t have a press agent behind it so the music papers were confused. As the Bob Dylan song says ‘Well, you know something’s happening but you don’t know what it is. Do you Mr. Jones?’

“Basically, I think it was the sound of punk moving out of the ghettos it had allowed itself to fall into. Maybe it was the birth of Goth and maybe it was just a tree branching out into a wider range of possibilities. Richard [Cabut] North wrote his very passionate article for the NME but its contents were overshadowed by those two dread words on the cover.

“Actually, it would have made a good cover for 2000AD with Judge Dredd pushing the barrel of his gun up the nostril of some guy with a Robert Smith hairdo. “Are you Positive, Punk?”

“It was just a label that didn’t stick because those words are essentially meaningless. The article itself is titled Punk Warriors and that is equally meaningless. If a sub editor had plastered the words “The New Noise Terrorists” across the cover they would have probably had a better response even though such a phrase would also be quite meaningless. It’s just that everyone would be queuing up to be called a “New Noise Terrorist”.

“Maybe I missed my calling in advertising.”

By this time in 1983 the group had been together for some three years. Though none of it was released until 1984’s “Life After Death” cassette, the group had been self-documenting on tape all the while.

Bob, “The first line up for the band was complete by early 1980 and we recorded our first demo that year. We scraped some money together and tried to record a demo tape at Alaska studios. The results were dreadful - bad enough to make you want to throw your instrument in the dustbin. Some guy from Essex actually stole the one copy we had and we were eternally in his debt. I hope he recorded something off of the radio over it.

“Why was it so bad? Well, I’m sure some bad chemicals were involved but, more importantly, no-one behind the desk had a fucking clue what the music was supposed to sound like. They looked at us as if we were the scum of the earth. Even 999 (who were rehearsing next door) tried to hide from us. The management wanted us out as quickly as possible. We recorded two songs (No Allegiance and Paradise) in about fifteen minutes including guitar and vocal overdubs. Go to whoa and no second takes or sound checks. Then they told us to fuck off and come back the next day to pick up the tape.

“The result was all heavily treated vocals and cardboard box sounding drums. The bass was audible but the guitar was sweetened and distortion free. They had made me plug directly into the desk with the promise of adding distortion later.

“These days, with a bit more experience, I know that it is difficult to record this kind of punk music. The guitars present as a constant barrage of chords which fight for the frequency space of the vocals. A lot of the early punk tended to chug along on the bottom three guitar strings but the stuff that we played let all the strings ring out with a heavy treble bias. As I said before, I’d taught myself to play by listening to ‘White Light White Heat’.

“Having noted those difficulties in recording techniques, I am still certain that a deaf gorilla could have done a better job than those guys at Alaska. All they seemed interested in doing was separating bands from their cash. They told you they’d do you a demo tape for about forty five quid or something. This was when the dole was about fifteen pounds ninety a week.

“Even to this day, I think the largest part of the music industry is solely designed with the purpose of preying on the musical aspirations of the young.

“We just cassette recorded after that for a while. Some of those recordings can be heard on the ‘Life After Death’ cassette. I quite enjoy listening to our version of ‘Louie Louie’ even though it is decidedly lo-fi. It was certainly a better result than the Alaska studio fiasco.

“In 1982 we went into Starforce Studios, an eight track at Clapham Junction. The results were an improvement but the sound remained quite thin. Too many engineers are fixated with clarity and it sucks the life out of things. On ‘Life After Death’ you can hear some of these recordings.

We then went to Oxy and the Moron’s basement and recorded on a four track Portastudio. We were much happier with the sound we got there. The guitars were rougher and there was more spill. These too are on ‘Life After Death’.”

The first official release from Blood And Roses would be the “Love Under Will” 12” EP on Kamera.

Bob, “In fact, “Love Under Will” was released in 1983. Our low budget demo recording had convinced us we needed better resources to record so self financed releases were out of the question. Besides we had no money. I can’t even hint at how little money we had. We were all on the dole and the money was always gone the day after we got it. Kamera offered us a deal and we jumped on it. Anagram had also had their feelers out but that hadn’t amounted to anything.”

Lisa, “‘Love Under Will’ always went down well at gigs, right sentiment. Crowley from the little I know of him was another one looking for his own way. Searching for something more than we are allowed to look for. From whatever means possible he had the balls or insanity to go to the extremes that sometimes it takes. whether he found it or not who can say but bless him he gave it a go in a time when people were even more closed up than they are now. To me it meant do whatever it takes in your own way, under your own Will.

“Recording it was great. It was the first proper studio and we were such a mass of freaks. The two producers in there didn’t even want to share the same room with us so luckily for us we got Ralph Jezzard to do his producing debut and he got out of making coffee and tea all day. He was only 16 but had his own ideas about music and was really patient when one of the band would nip off to score or find a chemist or pub.

“We were all well pleased and was the first time any of us had heard ourselves before.”

The four-song EP (the title track, “Spit Upon Your Grave” and two versions of “Necromantra”) is a most auspicious debut record. Driven by the great title track, something of a darker version of “Breathless” with a Dolls-like drive, the record is most unique for it’s imagery and cryptic lyrics and liner notes.

Bob, “‘Do what thou Wilt Shall be the Whole of the Law, Love is the Law, Love Under Will’ is a quote from The Book of the Law. The mythology is that Crowley “received” the Book of the Law as a holy text from his guardian angel but I prefer to think of this as allegorical. This is the kind of thing one says when one thinks about creating a religion and I am not interested in religion. That doesn’t mean I am not interested by the philosophies represented by these religions.

“The song ‘Love Under Will’ however, has its origin in Crowley’s novel ‘Diary of a Drug Fiend.’ In the book, an addict is cured by finding a purpose in his life through following Crowley’s doctrine. Now, I haven’t been a saint in the drugs department but there was one thing I had noticed. The more stuff I was doing with the band, the less interest I had in getting off my face. I started working pretty hard with Blood and Roses and was pretty much straight during the time I played with them. If we’re talking about the period before or immediately after, that’s a whole different ball game.

“Give away lines like “Chinese water bites at me” may hint at both the famous torture and certain extracts of the fruit of the poppy.

“The sleeve notes are influenced diatribe but influenced as much by anarchist philosophies as by Crowley. Certain magickal musicians have described these notes as hippy drivel but these are the kind of guys who are a little too overly enthusiastic about Norse mythology for their own good – if you catch my drift. Once again, there was an influence drawn from the linear notes of ‘The Psychedelic Sounds of the Thirteenth Floor Elevators’ at work but, looking back , the words are quite touchingly naive and passionate. I think the music says it better but I’m certainly not ashamed by what’s written there.”

For such serious content, the music seems almost contradictory being as upbeat and structurally rock-n-roll.

Bob, “Firstly, much of the early Blood and Roses material was in this style musically. “Curse On You”, “Paradise” an d “Jesus” all fitted into this style as did the cover versions we played like “Strychnine” and “Louie Louie”. The rolling drums of later material came further down the track. I think it is safe to say that this was one of the few examples of this form we got around to recording.

“Musically. I hear the Thirteenth Floor Elevator’s “Roller Coaster” played over a first album Stooges bass line and sped up to Ramone’s speed. Throw in a Johnny Thunder’s guitar solo for icing and I think you’ve pretty much got it. I’ve always wanted to do a version of it more at a dirge speed.”

The track “Spit Upon Your Grave” is credited as a collaboration between the entire band while the title (as well as Blood And Roses’ predilection towards horror and b-movies) suggests the name of the cult, rape/revenge film “I Spit On Your Grave” AKA “Day of The Woman”.

Bob, “In actual fact, I think a long like “Some Like it Hot” is more an example of a song writing collaboration than “Spit on your Grave” because the song writing credit emerges out of the fact that the music was initially built up out of a jam.

“The lyrics were written in advance. There was a fair bit of debate and hysteria in the air about so called “Video Nasties”. A lot of the pressure was emerging from right wing Christian groups and Mary Whitehouse would have been their poster child if only she was a hundred years younger and they had found a much larger sheet of paper to hold her bulk.

“The lyrics were constructed using a variation on Burrough’s cut up technique. I took a newspaper article on one of Whitehouse’s attacks on films like “Driller Killer” and “I spit on your grave.” I found a paragraph on medieval witch hunts and wrote a page of utterly pornographic filth. I cut them up and played with the words.It wasn’t entirely random. I was looking to make connections with phrases. I was hoping to make the song a kind of Sister Ray and so I convinced everyone to jam a melody. The final form of the song isn’t too different to the first jam session though I did add those guitar riffs later to give it more form.

“For the record, I don’t believe in the censorship of art. I don’t believe in classifications. Despite their vile reputations, I believe there is great artistic merit in films like “Driller Killer”, “Cannibal Holocaust”, “Salo”, “Caligula (Uncut)” and “Baise Moi”. All these films have been or remained banned in various parts of the world. Unfortunately, I think ‘I Spit On Your Grave’ is vile exploitation fodder of the lowest kind. Over the years it seems to have gained some kind of feminist credibility. However, I suspect the feminists in question are really seedy old men whose only interest is masturbation and then justifying themselves on the internet. Whilst I have no problem with masturbation in itself, I do have problems with anyone who would masturbate whilst this was on their television. Do I want the film banned? Of course not. If I don’t like a film, I don’t have to watch it. Besides, I might watch it again one day and see something in it I didn’t see before. Perhaps I will see a different sub text rather than the all too obvious cross referencing of sex, violence and death. I doubt it.”

She grips to silent paranoia

A victim of the changing times

She killed the girl her so called lover

And drowned in seas of rhythm rhyme

And as she lies in her death mask

I spit upon her grave

Finally, the cover art reconfirmed the lyrical sentiments.

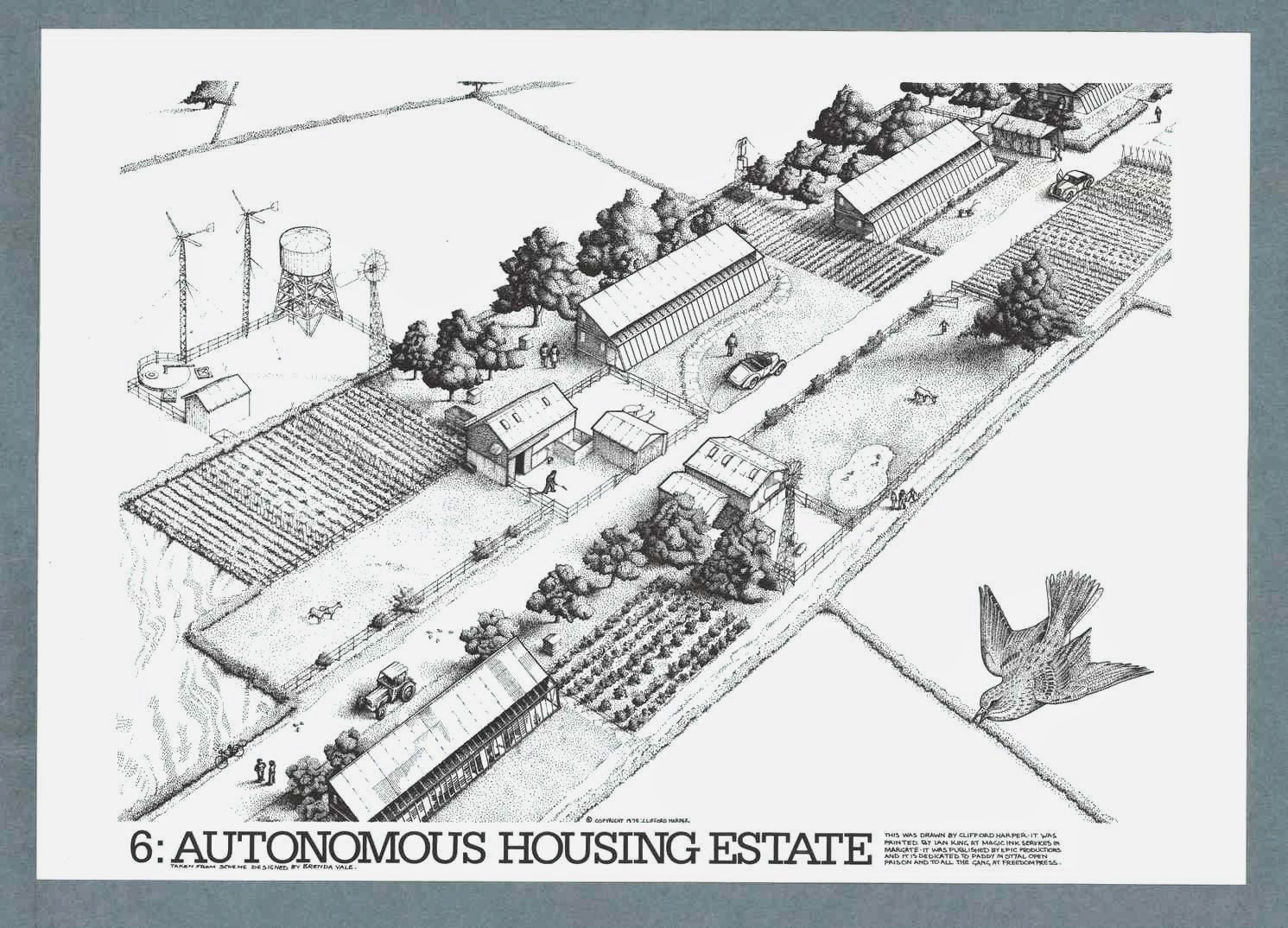

Bob, “That was drawn by Dave and Fod but I’d sort of told them what was supposed to be in the picture. They kind of ran with the theme. The central colour concept came as a tribute to the first “Thirteenth Floor Elevator” album. In many ways, I held that up as the central totem even though I don’t think anyone even had a copy at that point of time. I wanted a semi mystical sleave notes and a psychedelic cover but the printers shied away from the exactly specified colour shades because they thought the original red and green clashed too much and we must have made a mistake.

“The dancing skeletons stabbing each other in the back were symbolic of how the world seemed to be. It related to the song Necromantra. You could take it as superpowers, businessmen or lovers. The deceit of their actions had led them to mutual destruction. The exploding clock suggested time was running out.

“The front cover also contained the planetary symbols for Jupiter, Mercury and Venus. (Jupiter because this was a commercial endeavor and the success of the message was reliant on successful entry in the market place. Mercury as the messenger and the creator of musical instruments and Venus, of course, for love.)

“The rear cover depicts a Golden Horus framed by the signs of the zodiac and contained within a Yin and Yang symbol. Fairly straight forward imagery, really, centered around a central theme of balance. A problem on the front cover and a solution on the rear.”

In many ways, the themes of this record further reflected some of the other interests unique to the Kill Your Pet Puppy group.

Bob, “I know a lot of people have trouble with this Magick and mysticism stuff but it is probably best addressed in terms of a separate language. Through the use of the short cuts of symbolism, I can communicate a series of ideas far easier than I can through conventional words. If I use terms like Bat Cave, Goth and Anarcho Punk, I equally create a kind of short hand. If I’m writing to you, you immediately recognise those terms and we can convey broad concepts easily. With other people, If I told them that The Specimen were a kind of Bat Cave band they’d think of Adam West and Burt Ward.

“For me, a great part of the appeal of Crowley’s philosophy came out of what was lacking in Anarchist philosophies. Whilst Anarchists spent much time identifying power structures and talked about the corrupt nature of the system, there was very little thought about how individuals could find a way to define themselves in terms outside of the system. I think Crass’ overall popularity would have dipped substantially if their set list had contained such titles as “Let’s plant the crops”, “Together we can make a windmill” and “I’m happy cleaning the latrine.” Ultimately, these are the your major concerns when the revolution comes and they don’t fit into the romantic fantasy.

“Crowley talked about looking into yourself and finding your strengths and developing them. If this sounds like the modern “literature” that clogs up the self help section of your book shop, that’s not surprising. These are ideas that have now permeated the main stream but in a form that is driven towards financial rather than personal reward.

“Do I believe in spells and magic charms? Most definitely. But not in the way you might understand the concept. To write replies to your questions, I had to go through the ritual of setting up my computer and gathering my reference material so I could make sure I didn’t misspell anyone’s name. It is a spell to achieve a recognized goal. Likewise, charms remind me of purpose and my decision to take a certain path. They are tools to help me achieve what it is I want to achieve.”

The following year, the group released the aforementioned “Life After Death” cassette on 96 Tapes, a cassette only label that released music from Subhumans, Faction, The Mob and others.

Bob, “Either Andy Martin or Rob had already put out a cassette with a live performance at the Clarendon. The Mob were on one side and we were on the other. It wasn’t like a contract thing. It was all pretty underground. I remember being asked and I just said okay. It was no big deal and there was no money involved. I just wanted people to hear us.

“’Life after Death’ emerged because I was being literally inundated with blank cassettes asking for copies of demos. When it got to the point that I seemed to be doing ten hour days answering mail and dubbing cassettes, I think it would be fair to say I’d had enough.

“Rob had been in a band called Faction with Fod (Love Under Will artwork) and Martin who both lived upstairs from me. I can’t remember if Faction ever got around to playing but I do remember sitting under their rehearsals. Rob was already doing 96 Tapes and he offered to take over responsibility. It wasn’t a money thing but a lot of tapes went out and no-one was more surprised than me when the thing got a five star review in Sounds.”

The tenth release for this extremely successful tape label that would be related to All The Madmen, the group had stumbled into the peak of cassette culture.

Bob, “I think we stumbled in by accident and found ourselves right at the cutting edge. Cassettes were like how the internet is now. It was a way to distribute music without the constraints of capital or industry. Of course, the internet is becoming more difficult now as it becomes more of a business thing.”

With the success of their first 12” and a distribution deal with Communique, the group released their 1985 follow-up single on their own Audiodrome Records.

Bob, “Essentially, we were Audiodrome records. The name came as a variation on the title of David Cronenberg’s film Videodrome. In the run-out of the original album, the words “Long Live the New Flesh” are carved in tribute. The theory was we were creating music that would bury its way into people’s head and change them inexplicably just as the hidden signal on the television had fucked with James Wood in the film. Whilst this is utterly preposterous in reality, this is essentially the true nature and purpose of all art; to make a connection between artist and audience that is some way affecting I guess you could call Audiodrome Records an allegorical record company. Because it targets itself directly to emotions, I believe that music has the potential to invoke a revolutionary change of mind and spirit. If Blood and Roses and Audiodrome had a mission statement, it involved the breakdown of the corporate control mechanism; the “signal” within the music triggered a response that led to liberation, of course, there was no real signal. This was a metaphor for what we perceived as the spirit or emotional core of the music.

“Audiodrome came about because Communiqué in Norwich was willing to distribute. We simply did not have the resources to fund a record label. Communiqué provided an advance to record and, based off of that, they distributed a certain number of records. There was supposed to then be further negotiations if they wanted to distribute more. Despite watching twenty copies of it vanish from the Virgin Megastore in Oxford Street in a day and it selling out everywhere, it was never repressed even after it got a five star review in Sounds.”

The first release for this new label was the “(Some) Like It Hot” 7” and 12” single.

Lisa, “Love, Sex, Drugs ,Pleasure, Pain. Whatever makes you feel. I suppose to me, some like it hot means the extremes; obsession, possession. To drink from whichever vessel you’re drinking from until it’s empty and then move on.

“Very vampiric in a lot of ways. Like a lot of things sometimes if you lay things out too clearly about what you might be doing they wont draw their own picture.”

Bob, “Lyrically, I wrote one verse and the Chorus so I’ll only talk about the bits I wrote. You can ask Lisa about the verse she wrote.

“I was fairly obviously writing about Sex; total mind fucking sex. The kind of sex that makes you utterly oblivious to the universe. The kind of sex where hours vanish and the desire to surrender to that oblivion and the feeling of soul deep completion that creates. It also touches on the darker side of those moments; obsession and addiction.

“Hardly world shaking stuff (unless you are in an environment where everybody else is writing sexless songs about the state of the world). The song is just called “Some Like it Hot” without stupid brackets. In the mastering studio, there was some concern this might be confused with the Duran Duran spinoff band (Power Station?) single of the same name that they’d mastered the week before. Cue stupid brackets.

“The run out on the seven inch vinyl bears the legend ‘No thanks to DD.’”

Summer screams of Soft Caress

The mounting of desire

The whispered breath of scented sweat

The fuel onto the fire

Musically, it’s one of their greatest results with Lisa’s perfect vocal delivery exactly suited to the bouncing, demented rockabilly meets Birthday Party riff.

Bob, “Musically, the song began with what became the bass line of the chorus. Ralph gave it to me and asked me if I could turn it into anything. He thought it sounded like a verse riff. I was really going for a kind of Glam/Rockabilly feel as I started to piece the rest of it together. Initially, it was just going to be a big T-rex meets the Stray Cats kind of thing relying on a verse riff with chords in the chorus. That, however, did sound a little too like the Birthday Party for its own good. That isn’t entirely surprising given the fact that we grew up in a very similar scene to similar TV and radio.

“I wasn’t completely happy until I tried the abrupt minor 7th Chord chops. I’d been listening to a lot of Chic and how they used rhythm guitar to drive the song – not that you’d notice by the brutal kind of chopping I employed.

“I think the music really suited Lisa’s style of vocal delivery perfectly and it shows in the phrasing of the words.”

Lisa, “Once again it was brilliant getting into the studio Every time we went in we learnt something new and something new got added to the sound. It’s like being given a big canvas to draw on with a totally different set of colors.

“I loved working out new harmonies and backing tracks. Had total trust in Ralph and he was just part of the band. Bob could put extra guitars over, exactly the way he wanted. Messing about with samples. Drums cutting in so you can feel them all running like an engine with the bass. Can’t speak for the others but I loved going in the studio.”

The 12” version of the single included a cover version of sorts with the band marching through the theme music from the film “Escape From New York”. In their live set, the group had been known to do other soundtrack material.

Bob, “We’d already been playing the theme from “Assault on Precinct 13” for a long time. It had started as just a jam and somehow become an intricate part of the set. We often opened with it and recorded it for the John Peel show. We then included it on the album. Quite simply, we did that because we liked the song and you couldn’t get it on a record. The Pet Shop Boy’s Neil Tennant (In his pre stardom capacity as scathing rock scribe) described it as a toneless drone before ripping the tune off for a Pet Shop Boys songs with no credit to the writer, John Carpenter.

“We were kind of experimenting with synthesizers, a device we had no access to outside of the studio. I had the rough idea of what I wanted the music to “Enough is Never Enough” to sound like but I wanted to try to recreate something first so I’d at least have half a clue to what I was doing. It was done very quickly by Ralph and I. He did the arpeggios and I did the rest. It only took an hour or two and we thought it would be good as a B-side. I still get a kick out of listening to it.

“How did I get interested in soundtrack music? Shit. Isn’t that the first kind of music any kid loves? They all run round the playground singing the songs from movies and TV (and now Playstation too). Soundtrack music is very evocative and that direct emotional connection it draws from an audience is something a musician will always be keen to plug into.”

While actually covering soundtrack material only made a few appearances in the group’s set, soundtrack music loomed large in the groups approach.

Bob, “On a personal level, I was very influenced by the music of Goblin (who scored the films of Dario Argento). The music for “Enough is Never Enough” came to me under the spell of there theme for ‘Suspiria’. Okay, it sounds nothing like it but I was trying to write something that would have that same kind of inevitable gravity. I’m talking about the recreation of an emotional response so it is very difficult to qualify this in words. I do know that, if you play “Enough is Never Enough” through some kick arse speakers, everyone in the room turns and pays attention when those first notes hit.